Few nations doing enough to protect people from extreme weather - IPCC author

19 November 2011

By Megan Rowling

LONDON (AlertNet) - Most countries are not acting fast enough to protect their people from extreme weather, and more major disasters will likely have to happen before governments start investing enough in safety, a leading climate change expert has warned.

Tom Mitchell, one of the lead authors of a report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) on managing the risks of extreme weather, whose main findings were issued on Friday, told AlertNet growing economic losses from such events are pushing some governments to take disaster risk reduction more seriously. But successful initiatives remain “isolated cases”.

"The danger, I fear, is that it takes a big event per country to really get the government to sharpen their focus around this area, and this probably means that we are looking at some very significant events that are going to happen around the world until governments wake up to this possibility," he said in an interview.

On the current trajectory, the international humanitarian system - already under pressure - will "eventually reach breaking point", with disasters causing increasing harm to the most vulnerable sectors of society, he warned.

Mitchell, who is head of climate change at the London-based Overseas Development Institute, said a growing number of countries are losing significant chunks of their gross domestic product (GDP) to damage from extreme weather events, which are expected to happen more often as greenhouse gas emissions warm the planet.

El Salvador's environment minister recently told Mitchell the Central American nation has suffered damage from excessive rainfall in the last two years equivalent to 6 percent of its GDP, for example.

"When we are starting to talk about that level of impact on economic growth on any one country, then we start to move this issue well outside of an environmental issue, and much more into a core issue around social wellbeing, economic growth and poverty," Mitchell said.

In many countries, responsibility for reducing the risk of disasters tends to lie with weaker ministries, such as environment, and it often takes "something genuinely shocking" to enlist more important, well-resourced government departments, like finance and planning, in the effort, he noted.

The summary of the report, which will be issued in full next year, says it is "likely" - a two-thirds chance or more - that maximum and minimum daily temperatures around the globe have already increased because of human influences, including man-made greenhouse gases, as have sea levels and coastal high waters. There is “medium confidence” - about a 50 percent chance - that human influences have intensified extreme rainfall.

And the IPCC predicts - with varying degrees of certainty - that some events, including heatwaves and heavy rainstorms, will happen more often in future and be of greater magnitude.

TEMPERATURE SPIKES 6-8 DEGREES HIGHER BY 2050?

"There are some quite startling findings around precipitation extremes and temperature extremes by the time you get to the middle of the century under the higher emissions scenarios, which we are currently following. (We are) even talking about temperature extreme increases in the region of 6, 7, 8 degrees Celsius," said Mitchell.

If the world does not move to cut its emissions of heat-trapping gases from today's levels, "then these types of extremes in weather that we now see once in 20 years will become not far off an annual occurrence," he added.

Mitchell said disasters and economic losses will likely increase, irrespective of climate change, as more people, assets and infrastructure are exposed to hazards because of population growth, urbanisation and changes in settlement patterns, with shifts towards the coast and into mega-deltas.

Some parts of the world will become "very difficult to live and work in", he warned, including low-lying atolls threatened by sea-level rise and regions affected by severe or recurring droughts.

But the socio-economic factors influencing disaster risk mean governments can take action now to better protect people in harm's way, Mitchell said - through more stringent land-use planning to stop construction on flood plains, for example, or helping vulnerable communities relocate if there is no other option.

Bangladesh is one country that has made big strides in recent decades in curbing deaths and property damage from cyclones by boosting civil defence and moving assets away from the coast, he added.

'LOW REGRETS' MEASURES PAY

Maarten van Aalst, another of the IPCC report's lead authors and director of the Netherlands-based Red Cross/Red Crescent Climate Centre, said "low regrets" measures can be adopted at both local and national levels to help people cope with the threat from disasters and climate change, now and in the future.

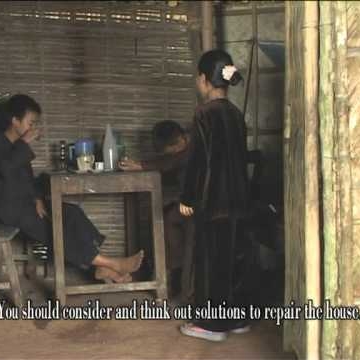

These include installing early warning systems, waterproofing and raising the level of huts, planting trees and stocking emergency supplies ahead of time.

"You can see rising risk in your face in many of these developing-country contexts – in terms of informal settlements, in rapidly urbanising cities... and we know to some extent what to do about them," he told AlertNet. "It's not always easy, but there are many angles that don't rely on very exact climate science to be able to address these rising risks."

Van Aalst said the Red Cross is working with communities around the world to strengthen their resilience to extreme weather, as well as talking with governments to promote a joined-up approach to disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation.

One major problem for the world's least-developed countries is that they have less weather and climate data available than richer nations for analysing and predicting past and future trends. That translates into a higher degree of uncertainty about what the poorest and most vulnerable people face.

"There is an inequality of risk, not just in that sense (of impacts), but also in the sense of ability to project future risk. We have much better data for Western Europe and North America than we have for most of Africa," van Aalst said.

PRACTICAL ACTION

Both authors said the IPCC report contains "worrying" findings for negotiators meeting at U.N. climate talks in Durban later this month. But van Aalst emphasised that it also offers "practical entry points" for managing changing climate risks that can bring quick wins for development.

"I hope this will allow a sense of optimism that, despite the difficult negotiations, a lot is possible in practice," he said.

The report does not estimate how much money governments can save by investing in steps to reduce the risk of disasters. The difficulty of quantifying losses that are avoided when disasters are prevented is widely regarded as one obstacle to calculating cost-benefit ratios.

Nonetheless, van Aalst said a rate of return ranging between 400 and 1,000 percent can be achieved on some, though not all, disaster reduction investments.

"The rates of return will be highest from the simplest measures at the most local level that are relatively low-cost and have a lot of also non-monetary impacts. If you start monetising them, you can get fantastic rates of return – if you start valuing human life, or not taking your daughter out of school to survive the next bad harvest," he said. "It's partly a cultural mindset change we need rather than just a hard economic analysis."