|

For more detailed

information contact DEVELOPMENT WORKSHOP France B.P. 13, 82110 Lauzerte,

France |

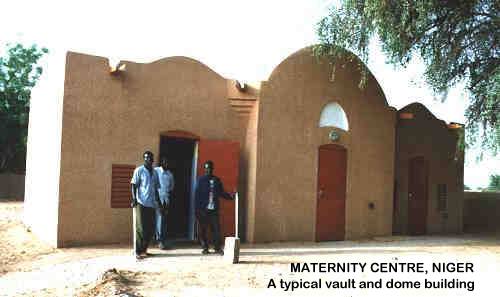

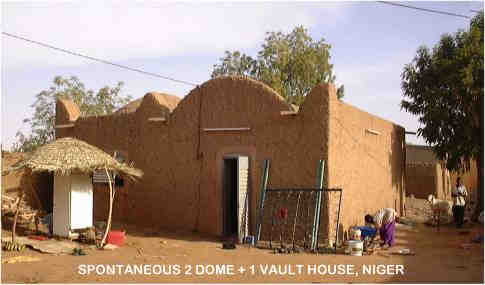

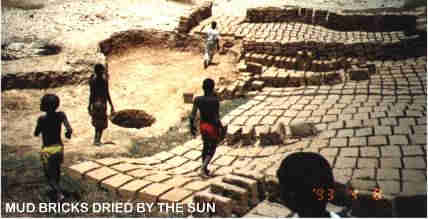

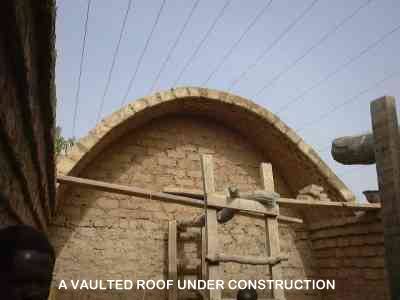

Woodless Construction - developing a sustainable alternative building method in the Sahel In the Sahel countries of West Africa, "Woodless Construction" is the name given to the construction of vault or dome roofed buildings using ordinary mud bricks.  The bricks for the walls and roofs are formed in simple rectangular moulds, smoothed by hand and dried in the open - a method habitually used in the region.  Both the vaults and the domes are built using techniques, which have their origin in Iran and Egypt. The most important characteristic of these roofs is that they are built without any supporting shuttering. Thus the entire structure - walls, lintels, and roofs - is built with locally available earth and based on a rich building tradition in the region.  | ||

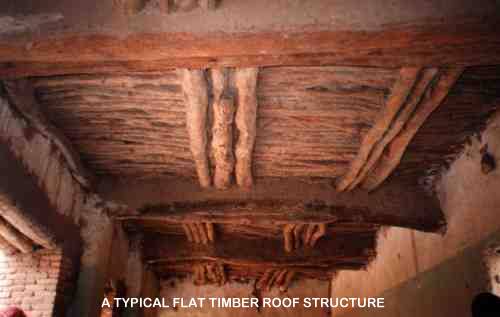

| Why Woodless Construction? The majority of rural and urban dwellings in the Sahel depend on the use of organic materials for the structure of the roof, and often for the walls as well in rural areas. Flat-roofed buildings typically use large beams and intermediary battens to provide the support for grass-woven mats and for compacted earth on the roof. Thatched roof structures consume even more. Surveys show that for almost all such structures the availability and quality of wood or branches has deteriorated markedly in the past twenty years(1).  A frequent complaint is that finding good wood has become extremely difficult. The Sahel has been blighted by years of drought that has contributed to the disappearance of trees, but the biggest single source of degradation is over-consumption by man. Fuel-wood is one major cause for concern, but wood for building is unquestionably the other. The wood used in building invariably requires cutting large tree trunks. The result: many tree species are totally now totally used up, and in some areas whole forests have gone. Woodless Construction was introduced by Development Workshop into the Sahel to provide a viable, affordable and accessible alternative to this dual problem - how to alleviate pressure on the threatened natural resources of the Sahel and at the same time to make building by the population easier using resources realistically available. | |||

|

Sustainable

solutions take time: to listen, observe, adapt

One example: the brief but often violent rainstorms which are common in the Sahel during the rainy season require particular care in shaping roofs to ensure quick but controlled rainwater run-off. The high winds that accompany these storms drive the rain almost horizontally, and it is often the walls that need protection more than the roofs. Special attention therefore has to be paid to orientation and the choice of surface finishes, which are strongly influenced by local practice. | |||

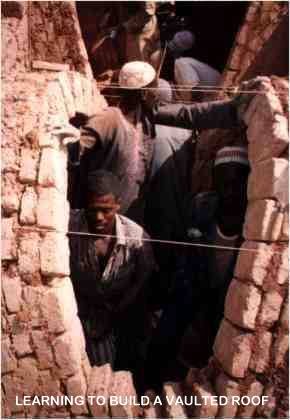

| Developing skills in the

community Skills development is at the heart of the process of introducing these techniques. Training is done today by local trainers, who started as village builders, or even unskilled labour, and who have worked up through a supported process of repeated training opportunities and on the job learning and experience.

Certainly new ideas are suggested and introduced, but where possible these are used in conjunction with local techniques. As an example woodless construction uses local bricks sizes as available for wall building when these are suitable rather than always insisting on special dimensions for bricks and moulds. In turn, the brick is the unit that determines the dimensions of the building, rather than metric dimensions which are unfamiliar to local builders. | |||

|

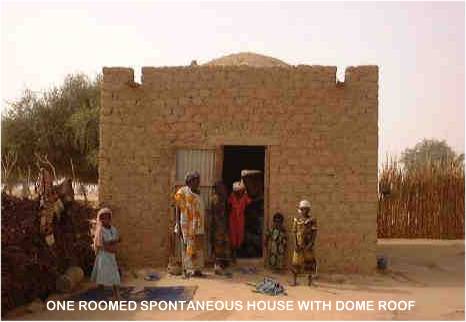

Local confidence

leading to sustained local use

The process can take

several years, and in a year when there is a poor harvest, very little

building may take place. The example of buildings for slightly better off

families in poor communities is also important in showing local

confidence. | |||

|

(1) On-going surveys and previous work undertaken in Mali and Niger (e.g. Development Workshop, Evaluation des bâtiments et des techniques de construction dans le Cercle de Youvarou, a DW/UICN report, 1991, 45 pp., illus.); and in Niger (Hammer, D. Tunley, P. & Development Workshop, Iférouane - Habitat en Evolution, a DW/UICN/WWF report, 1991, 30 pp., illus.) (2) After ten years of experience using these technologies in Iran and Egypt where they have existed for centuries, Development Workshop introduced woodless vaults and domes to Niger in 1980 at the request of a small Canadian NGO, ISAID, in the context of a rural development programme. Much of the adaptation work in the early 1980's was done by Peter Tunley in Niger. Over the past 19 years, support has come from a variety of donors and partners, notably Danish International Development Aid (DANIDA) with IUCN, the Danish Red Cross and local Red Cross committees in Mali and Burkina Faso, European Development Funds, SOS Sahel, Lutheran World Relief, the ILO and WWF. |

|||

| This text draws in part on a text published by the German Appropriate Technology Exchange (GATE) in 1995, in the BASIN case study series, and their generous support is acknowledged. The Woodless Construction project in Niger was awarded the UN Habitat Scroll of Honour in 1992. |